This is essentially the tagline for the recent Struzan documentary, Drew: The Man Behind the Poster, which I found a bit disappointing. Most of the people they talked to were directors and actors who knew little about illustration or its history. I'm sorry, but when I watch a documentary on illustration, Steve Guttenberg just isn't the guy I want to hear from. There were a couple of illustrators thrown in, like Greg Hildebrandt and Charles White III, but they were given little opportunity to talk about the form. It was mostly just an endless stream of praise.

It is true Struzan is one of the great movie poster artists, and many of his images will be forever associated with the films that they promoted, which is no small accomplishment. And while I do think he deserves to be celebrated, I don't think he deserves to be canonized, which is what the film seemed to have set out to do.

But the documentary doesn't tell the full story. While it's acknowledged that Struzan was asked at times to emulate other artists, it neglects to mention that in beginning of his career, this was almost all that he did. It also neglects to mention Struzan's three principal influences: J.C. Leyendecker, Bob Peak, and not insignificantly, Barron Storey.

Early Influences

At the beginning of Drew Struzan's career, when he was doing album covers for the design studio, Pacific Eye and Ear, he was still finding his voice. Like any artist at the beginning of their career, he emulated others. Here's one of his most popular pieces at the time, for Black Sabbath,

|

| From Struzan's Black Sabbath album cover for Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath |

This one had a little bit of Salvador Dali,

Channeled through Maxfield Parrish (below). In fact, that figure kneeling on the right on the Sabbath cover looks suspiciously like this one, same light source and everything:

Here's another one:

This one looks like Parrish on the borders, with a little Bernie Fuchs on the interior figures. Here's Bernie Fuchs:

Struzan was always more a draftsman than a painter, and these inspirations tended to take on a more line and plane oriented character than a painterly one.

Struzan broke though with this image of Alice Cooper on Cooper's album, Welcome to My Nightmare. This one got Struzan his first movie poster gig, and, as mentioned, it was movie posters where Struzan truly made his mark.

But while most of his album cover work only showed shades of his influences, this image was a straight up homage to J.C. Leyendecker. (The fact that this wasn't mentioned in the documentary is just astounding to me). And here's Leyendecker:

Though it wasn't the first time he'd done Leyendecker:

And for a while this became Struzan's thing. You can see it particularly strongly in this early Star Wars poster, a collaboration with Charles White III. White did the robots and shiny stuff, and Drew did the figures:

This was where White also introduced Struzan to the airbrush which would become a big part of Struzan's technique later on. But again, the difference between Struzan's Leyendecker and Leyendecker's Leyendecker is that Struzan was more of a draftsman than a painter. He was able to emulate some superficial elements of Lyendecker's style, but never really got what made Leyendecker a real painter. Not that Struzan didn't eventually gain a certain facility with paint and painterly techniques, but at this point, he was more an imitator than his own artist.

Struzan, at the time, was so good at imitating Leyendecker, they asked him to emulate other classic illustrators like Norman Rockwell:

And notably, Bob Peak:

And this was when Peak was at the height of his popularity. It was a case of "you can't get Peak? Well this guy does a good Peak imitation and he's cheaper. Hire him." Here's some Peak for comparison:

It was from Peak that Struzan got his talent for montage, and who, beside's Storey, would remain one of the greatest influences on his work.

Enter: Barron Storey

Barron Storey, my old teacher, always said that he never learned to paint. Which didn't mean he hadn't learned some of the principals of painting. But he is, like Struzan, at heart a draftsman. Storey was a contemporary of Struzan, and while he started out wearing his influences on his sleeve like Struzan, he soon evolved his own style. Here's Storey:

Looking a little like early Peak:

Storey's style was invention born of necessity. Because he felt he lacked the facility to paint, he used line to emulate the mass and body of paint. Here's one of his Time covers:

He approached rendering with slashes of hash marks to define planes rather than painterly brush strokes to describe masses.

And another famous one that's pure draftsmanship, of Howard Hughes, according to Storey, done right at the Time offices the night Hughes died. All he had to work from were what photos existed on file and a description of Hughes' given on the phone from a witness, since Hughes hadn't been seen in public for years:

And it remains one of the most iconic images of the late Hughes, which is remarkable considering that Storey could only speculate about what Hughes looked like based on photos more than a decade out of date.

In a painterly approach (say, Rembrandt), the body of the paint conveys mass. Sometimes a single stroke will describe an eyelid or the bridge of a nose. In a tighter rendering where brushstrokes are less desirable, the paint builds value with blended tone applied as you might with charcoal. This classic approach is as old as the Renaissance and still common among artists today (sometimes achieved with glazes of thin paint), though many artists use a combination of both approaches. Then there are artists who work in the tradition of Durer, where line is built up in layered patterns of methodical cross-hatching. Tim O'Brian is a good contemporary example of an illustrator who uses this method, and Paul Cadmus in the fine art world.

Storey's approach was like none of these, though it had more of a relationship to Durer than the more painterly Rembrandt. But it wasn't one he had entirely invented. A less methodical approach to line can be seen as early as Daumier. But when I think of Storey I think of Italian pen and ink illustrator/comics artist Toppi and South American comics artist Breccia, and since Storey was a fan of comics, I imagine he was likely aware of Toppi. Here's one from Toppi:

I imagine these guys too, have a precedent for this approach to line that I'm not aware of, so if anyone has any insight I'd be curious what you think, but in general it seems to come from turn of the century expressionism.

Storey claimed Robert Weaver, his teacher, as his greatest influence, but the subtlety and spareness of Weaver wasn't Storey's strong suit. Storey is more about obsessive detail and an improvisational approach to rendering, Never applying the same stroke twice or in quite the same way. When not doing a single subject, like a portrait, his compositions could be dense with elaborately rendered imagery. Weaver was more about reportage, while Storey tended to live more in his head. Where Weaver observed, Storey invented. But ultimately the connection between Struzan and Storey is not one of content, but of craft.

Another portrait from Time:

And a detail:

And his classic Lord of the Flies cover:

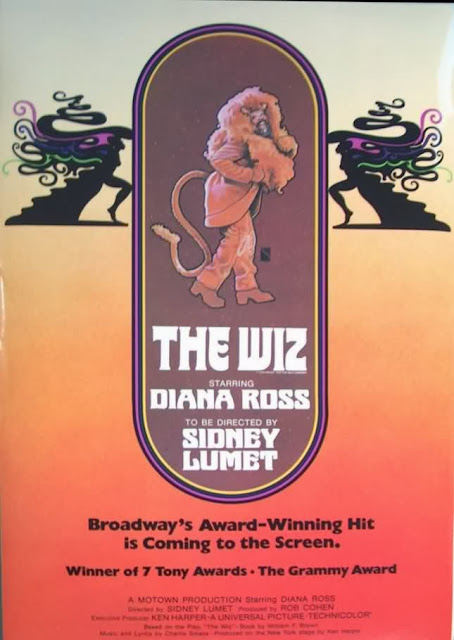

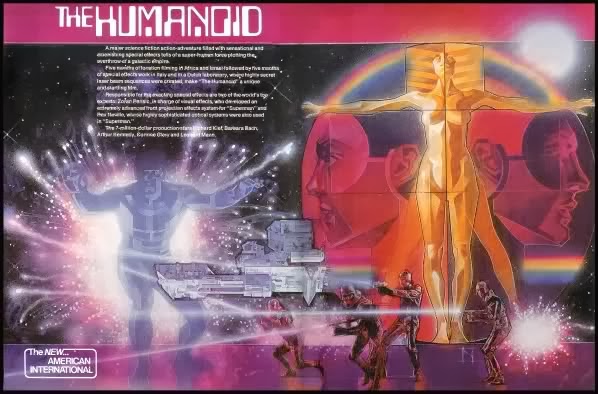

By the late 70s Struzan was already veering away from the Lyendecker and Peak influence and into his own style (though this one has a hint of Syd Mead):

I think Struzan was very much aware of Storey at the time, and picked up on what he was doing. And that's when Struzan's style really became his own.

Take a closer look:

And this is when Struzan's career really started to take off. There was his talent for idealized portraiture and montage borrowed from Bob Peak, and then there was the influence of Storey. He didn't just pick up Barron Storey's technique, like he had Leyendecker's, but his inventive approach to line and mixed media. It wasn't the materials, it was the approach. Mixed media was not the point. Since he was more a draftsman than a painter, Struzan got Storey. Or at least, a certain aspect of what Storey was good at. Not that he emulated Storey entirely, or gave up the more painterly aspects of his work, but he was able to incorporate Storey's approach to line and form in a way that served his affinity for drawing.

Here are a few greatest hits with details:

And more recently:

His approach is more methodical, but you can see him getting more bold and improvisational in some of the later pieces, but never quite to the degree of Storey.

And that's about where it ended with Struzan, who has recently retired. But Storey kept on experimenting and growing. Both in his professional work (this one still from the 70s):

And in his personal work, particularly in his sketchbooks, which he draws in every day, a few of which I had the pleasure of checking out in person while I was in school (and they look even better in person.) Here's some examples:

And he has been and continues to be a huge influence on some of the best contemporary illustrators working today:

|

| Bill Sienkiewicz |

|

| Kent Williams |

|

| Dave McKean |

.jpg)

+Original.jpg)

+4.jpg)

Wow! I'm sorry, I studied with both of these men (Barron and Drew) and you simply could not be more off target. Drew is an amazing draftsman and so is Barron, but that is where the connection and similarities end. Barron is a true artist, tortured and complex, searching for the shadows. Drew is a true craftsmen, looking for design and pattern and light. You simply need only see their two working environments (studios) and you can catch a glimpse of who they are. If you're looking to elevate Barron's status and place in the world illustration, you'd be right to do so- he is an unsung hero, but I think you'd find Barron would prefer to be called a fine artist rather than an illustrator.

ReplyDeleteI'm not in the habit of posting anonymous comments, but I will address this one just this once:

ReplyDeleteAll I was suggesting was that Struzan picked up on some of Barron's method and incorporated it into his own, and that this is part of how he forged his own identity as an illustrator. That before this, he was more of an imitator, and hadn't really found his own style. But you are correct: his work isn't like Barron's at all, and the two have very different objectives with their work.

Personalities aren't really relevant to this discussion, but as you know, I had Barron as a teacher as well, and I agree, he has a certain penchant for drama. I also think he's both an accomplished illustrator and fine artist. I wouldn't discount one for the other.

I don't have any agenda here outside of exploring Struzan's influences and spotting what I think is a connection between the two, as you say, very very different artists.

Incidentally, Barron or Petra reposted this on Facebook, so one of them must have at least found it intriguing.

Jed, I too had Barron as a teacher and one couldn't help be influenced whether you liked him or not. I never even met Drew and, at first, I thought you were off base putting the two artists together in the same paragraph, but you did a fine job showing how many of us who were learning our craft were influenced by those great illustrators of that time. It was a time of great cross-pollination. I really enjoyed the close-ups of each styles and how over time each artist found themselves and their own way of visual problem solving.

DeleteAlthough I never made the connection, clearly your observation about Barron's draftsmanship is, in my humble opinion, spot on. Barron once told me one of his early heroes was the New York illustrator, Robert Weaver. I never understood that statement because the "Barron" I knew back in the mid to late seventies was such a realistic renderer.

Now, I think I better understand what he meant and your observations about his style, as well as Drew's, has helped me to relive or, at least, revisit those many influences. Influences we all are susceptible to.

Thanks for the article… tell Barron and Petra, hello for me!

Jed interesting observations. I think they are right on point.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed this educational insight that builds into my own knowledge...based on various observations from various eyes

ReplyDeleteThanks Ben, Tim, and "prettylines!"

ReplyDeleteI admit that it's a provocative title, and have gotten some negative flack from people familiar with both artists, but I'm finding that this tends to be more of an initial reaction than a lasting one once they've read my argument. For the most part, anyway. I've gotten positive support from at least two of the illustrators I've mentioned in the essay, in passing, which suggests I'm not entirely off base. But for whatever reason, it seems to have hit a nerve, and the post has been getting a fair amount of traffic in the last few days.

And Ben: I'm no better acquainted with Barron or Petra than I imagine you are, so you are just as welcome to tell them "hello" yourself on Facebook! Just look up Barron's name. I mentioned Petra because from what I understand, she runs his Facebook page. But I imagine he peeks in from time to time. I'm sure he'd love to hear from you!

Being an illustrator in the 70s and 80s I was influenced heavily by Bernie Fuchs, Bart Forbes, Robert Heindel and others. I look back on my body of work during this time and the influences are obvious as they are in Struzan's influence by Story. But Struzan found his own path and developed a strong following all his own and in the process created a whole generation of illustrators that copied him. That's how it goes. Rare is the illustrator or fine artist that comes out of the blocks with his own undeniable style. The strength of any true artist is to eventually find your own path.

ReplyDeleteWhich very nicely summarizes the thesis of my essay. :)

ReplyDeleteHi Jed-

ReplyDeleteI'm another ACCD grad from the late '70s and another Barron Storey student. After graduating in '79 I trolled shallower depths of the same waters that Drew did in and around Hollywood. I never knew Drew personally but I worked in the same business. While I take no issue with any of your comments about Barron's talent or his work, based on the time I spent with him I can say with some certainty that he would have been a complete and total failure as a movie poster artist. I understand that your article was making points about style and technique. My point is that being a movie poster artist is 70% ability to cope with and perform in the worst and most abusive conditions imaginable and 30% talent and training. In my own case my shortcomings were mostly in my ability to function at my highest level deprived of sleep and subjected to the pummeling of the movie business. Many endeavors are full of talented individuals who crack under the specific pressures of that discipline. So I say yes yes and yes to all of your observations about Drew's 'borrowing' of style and technique from Leyendecker, Peak, Storey and others. I simply want to point out that in the context of Drew's career and the contribution that he made to film advertising, that doesn't matter. It was his amazing facility and adaptability along with his ability to perform under pressure that made him one of the best illustrators of his time.

"Look son, being a good shot, being quick with a pistol, that don't do no harm, but it don't mean much next to being cool-headed. A man who will keep his head and not get rattled under fire, like as not, he'll kill ya. It ain't so easy to shoot a man anyhow, especially if the son-of-a-bitch is shootin' back at you."

-Little Bill Daggett, "Unforgiven"

Good analysis. I think one influence you left out was Richard Amsel.

ReplyDeleteBest comment on my facebook feed came from Michael Backus, another AC illustrator of my generation: "Despite the differences, [I was] amazed at how similar the life was [to that of lesser-known illustrators]: difficult clients, nightmare deadlines requiring little sleep for days or weeks, thieving parasites who take advantage of creative people and their naïveté, the love of the work itself, and the sense of loss that we all feel at the death of this more than century old profession.

At various points in the documentary, especially when viewing Drew's brilliant work, I found myself feeling that old impulse to 'work on my book'. I quickly recognized it as a vestigial reaction, a conditioned response to a time gone by. Like a lost limb I still feel my old career, have phantom pain of the desire to get out there and get that big movie job. But I know the truth. There is no more movie illustration work. The day of the big name star illustrator has passed. Movie posters are now ground out by nameless technicians, clicking away on computers as I am now.

'Drew: The Man Behind The Poster' is worth a look, if for no other reason than to get a look at a way of life that has passed, like the Plains Indians, printed newspapers or industrialists with a sense of social responsibility."

Someone else mentioned Amsel, and it does seem as though those two were head to head for a while, and Amsel shares a lot of the same influences. Amsel's success preceded Struzan's, so I imagine that Amsel did rub off on Struzan more than a little, and Amsels later work is often mistaken (even by me) for Struzans. I had always thought the famous Raiders of the Lost Ark poster was Struzans, and even posted it above before someone pointed out it was Amsels and I pulled it.

ReplyDeleteJed:

DeleteI have always been a big fan of Richard Amsel's work. While Drew's talent is undeniable, it did seem strange that he credit's no one with having any influence on his work. All of the artists that you mentioned such as Bob Peak and JC Leyendecker were either direct or indirect influences to Drew's work, I would also add Ted Coconis' work. But to have a documentary on his work and not mention Richard Amsel, the person whose work had the most influence on his, is mind boggling. Had Richard Amsel not passed away in 1985 I think that Drew would have had a much different career.

By the way, claiming that you didn't eat 5 days out of every week makes you sound crazy.

Hi Anonymous,

DeleteI whole-heatedly agree with your assertion of the influence Amsel had on Struzan's work. I have long thought this to be the case, and I thank you for validating my suspicions!

Dave Robinson

I, too, am a huge fan of Richard Amsel's, and was surprised his name wasn't included in this article. I heard the guy who runs the Amsel website has been shooting a feature documentary on him, but he won't confirm it publicly yet.

DeleteIt seems clear that Struzan was influenced by Amsel compositionally, but like most people he emulated, he used his own technique to achieve a result that resembled their style. For instance: Lyendecker. Struzan wasn't a very intuitive painter, and trying to emulate Lyendecker's painterly style didn't suit him.

DeleteEventually it seems like he was able to come up with a technique and formal method that was his own. But yes, it looks like he was still looking to another artist for direct inspiration, in this case, Amsel, using the "Struzan method" to emulate the compositional style of Amsel.

I'm with you up to the not eating thing. I think a lot of people tend to exaggerate their struggle--it's grandfather's disease, rather than actual craziness. As Bill Cosby used to say---his dad walked through the snow, uphill, both ways. And to some degree you really have to blame the documentarian. Struzan admits that he was asked to draw in a variety of styles and to emulate other artists. The documentarian couldn't pursued that angle a little more, but chose not to. My guess is that they simply didn't do their homework about the history of illustration and Struzan's place in it.

ReplyDeleteAmsel is, unfortunately, a very new discovery of mine, and came about as a result of writing this essay, so if I were to rewrite the essay, I'd probably devote serious attention to Amsel.

It's finally just confirmed that a film documentary on Amsel is being made. About friggin time.

DeleteThe Moonraker poster isn't Struzan.

ReplyDeleteGood catch! I'll have to go back and edit that.

ReplyDeleteTom Peak here.

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading!

ReplyDeleteHi Jed,

ReplyDeleteThis is a very inciteful article about an artist who has reached legendary status in American pop culture. Thank you for sharing it with us!

Struzan claims he was required by his publishers to render in other artists' styles early on his career. You can't fault him for that because he was just trying to earn a living. There is no disgrace in copying someone else's style, if that is what the client requires. However in some cases he went a bit further than just copying styles. He actually plagiarized J.C. Leyendecker's work in at least a couple of instances I know of (there may be more). For example, you can see outright copying of portions of Leyendecker's "Couple Descending Staircase" painting in Struzan's Tony Orlando album cover. Compare it closely to Leyendecker's painting at this url http://www.americanillustration.org/pressRelease/NMAI_Press_1_4_07.html

It's pretty obvious he copied Leyendecker's work if you ask me.

Here's another painting he "borrowed from. Compare the horse from Struzan's "Frisco Kid" poster to Leyendecker's Saturday Evening Post cover of George Washington (July 2, 1927). I've pasted the URLs below. The horse on the left has the same facial expression, and basic posturing as the one in Struzan's poster. Struzan changed the hoese's coloring, but it is still pretty damned close to Leyendecker's painting.

The Struzan URL is

http://drewstruzan.com/illustrated/portfolio/?fa=large&gid=923&mp&gallerystart=26&pagestart=1&type=mp&gs=2

The Layendecker URL is (You'll have to scroll down the page a bit to find this painting.)

http://poulwebb.blogspot.com/2015/04/j-c-leyendecker-part-5.html

I know Struzan has done some "iconic" stuff and I respect him for being who he is to popular culture. But I cannot abide plagiarism no matter where you are in your career. He has come into his own over the years, but it doesn't excuse him from having copied other artists' work. Of course he will never cop to it!

Sorry for the misspelling of the word "insightful".

DeleteAlso, the Struzan URL I submitted earlier was incorrect. Sorry about that. The correct URL is below.

Deletehttp://drewstruzan.com/illustrated/portfolio/fa=large&gid=923&mp&gallerystart=26&pagestart=1&type=mp&gs=2

Thank you! I think Drew was more of a draftsman than a painter, and he didn't "get" what guys like Lyendecker did, copying superficial elements of style, but unable to mimic painting technique. Ultimately he leaned on his strengths, and his more contemporary paintings have more of a drawing vocabulary like Storey.

ReplyDeleteIt's clear he was asked to draw in other artist's styles, but there's drawing in the manner of, drawing a tribute to, and then there's just swiping. He was guilty of a little too much of the later in his early career.

Jed I agree with you on all points! Thanks.

DeleteWell... Very interesting article. I knew the Leyendeker/Peak influences in the Struzan's work (so obvious), but didn't know the work of Storey, and crearly seems the MAIN influence in Drew (at least in some works). Certanly Amsel was another influence.

ReplyDeleteThe question is: ¿And?

EVERYBODY got influences (very obvious in some cases, not so obvious in other cases). Certanly Drew didn't invented a style, but a LOT of artists who grew up with his works (like me, heheheh) had a heavy 'Struzanian' influence: Ironically, Paul Shipper took advantage of the retirement of Drew Struzan to emulate/copy/tribute/borrow him (point by point) and, look him now, he is the "new Struzan" in Hollywood. A smart guy. And there is a LOT of "Struzanian" (not so) new artists in the industry now, and, in 20 or 30 years, we will see new artists "borrowing" the work of Paul Shipper, Kyle Lambert, Hugh Fleming, Eric Powell or Mark Raats (and, perhaps, ME, hahahah... i hope so!)

In other words, yes, i'm totally agree with your studement, and is very good to demystify our idols and bring them down to earth... but the Drew's talent (even to be a good copycat, we need talent to do) and his MASSIVE influence in a generation of artists, is unquestionable.

Cheers!

this was really interesting to read! i'm currently studying illustration at SJSU, where barron storey used to teach as well. i'd only really known about his sketchbook pages, so i had no clue he had such a big influence on the art atmosphere in general. i guess i shouldn't be too surprised though, because even in 2026 i (and my peers) continue to look at his art for inspiration.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comment! I went to SJSU as well, and Barron was my teacher. I was in the same class as David Chai, and John Clapp had just started teaching there. I think the department has really grown since then, with their great animation program, and it's really wonderful to see the job placement listings in their newsletter! We didn't have any of that. We were just set loose on the world, knowing very little about how to actually make a living in this industry. Most of my fellow graduates didn't go into illustration at all. There just weren't that many opportunities.

DeleteJust a few years ago Barron was inducted into the Society of Illustrator's Hall of Fame. It was also the first year I made it into the annual. That annual had a big feature on Barron, and I've always wondered if he saw my name in there and recognized that I'd been his student.

Good luck with your studies, And I wish you lots of success!